"Jenny Sparks" is one of those flashes. Writing superheroes is a lot like writing a sonnet. In a sonnet, to paraphrase Madeleine L'Engle in "A Wrinkle In Time," the writer must follow very strict rules regarding rhyme and meter, or else the poem can no longer be called a sonnet. But within those strict rules, the writer can say anything they wish. Similarly, with superheroes, a writer must stay within the parameters of the hero's personality, origin story, and universe. A Batman comic where Batman can fly and shoot laser beams from his eyes isn't really a Batman comic. Superman without the destruction of the planet Krypton isn't Superman. Wonder Woman without superpowers is Wonder Woman in the 60s, but that's a whole other problem. The point is, this is not 'Nam; there are rules. But within the parameters of those rules, the writer may say whatever they choose.

Writing superheroes is a lot like writing a sonnet. In a sonnet, to paraphrase Madeleine L'Engle in "A Wrinkle In Time," the writer must follow very strict rules regarding rhyme and meter, or else the poem can no longer be called a sonnet. But within those strict rules, the writer can say anything they wish. Similarly, with superheroes, a writer must stay within the parameters of the hero's personality, origin story, and universe. A Batman comic where Batman can fly and shoot laser beams from his eyes isn't really a Batman comic. Superman without the destruction of the planet Krypton isn't Superman. Wonder Woman without superpowers is Wonder Woman in the 60s, but that's a whole other problem. The point is, this is not 'Nam; there are rules. But within the parameters of those rules, the writer may say whatever they choose.

Here are the parameters of Jenny Sparks of Stormwatch as of Issue 44: she's 96 years old; she lives off booze and cigarettes; she's made of electricity; and she's the Spirit of the 20th Century. From these simple elements, in a single issue unconnected to any larger Stormwatch story lines, Warren Ellis and Tom Raney choose to deconstruct the superhero and the entire history of comic books. If anyone ever asks you, "What's this art form all about?" (I don't know exactly how this situation would arise, but let's assume it involves light projectile weaponry and a set of cat ears), you can just hand them "Jenny Sparks." As with Jack Hawksmoor, the God of Cities, Ellis christened his beloved Jenny Sparks with a title she didn't immediately live up to. "The Spirit of the 20th Century" spent the better part of "Force of Nature" being hungover, cranky, and impatient, a reluctant leader with such little regard for her boss that she won't even call him by his superhero name. But in "Lightning Strikes," we see her earn her title. "Jenny Sparks" is a frame story, with Jenny telling her fellow Stormwatch officer Battalion the story of her life, which just happens to be the story of comic books and superheroes from the 1920s to the present day. It is, as I've mentioned, brilliant on many levels, because as it turns out, Jenny isn't just any hero; she's ALL heroes, from the Depression-era dynamo to the Watchman-esque anti-hero.

As with Jack Hawksmoor, the God of Cities, Ellis christened his beloved Jenny Sparks with a title she didn't immediately live up to. "The Spirit of the 20th Century" spent the better part of "Force of Nature" being hungover, cranky, and impatient, a reluctant leader with such little regard for her boss that she won't even call him by his superhero name. But in "Lightning Strikes," we see her earn her title. "Jenny Sparks" is a frame story, with Jenny telling her fellow Stormwatch officer Battalion the story of her life, which just happens to be the story of comic books and superheroes from the 1920s to the present day. It is, as I've mentioned, brilliant on many levels, because as it turns out, Jenny isn't just any hero; she's ALL heroes, from the Depression-era dynamo to the Watchman-esque anti-hero.

For a change, I'm going to focus on Raney's contribution to this issue, because while Ellis's writing is, as usual, top-notch, it's the artwork that really makes this story work. Raney draws each era of Jenny's life in the style of the comic books famous and influential in that time, so her 1940s adventures look like Will Eisner's "The Spirit" and her 60s adventures recall Jack Kirby's early Marvel work. Jenny's story begins in

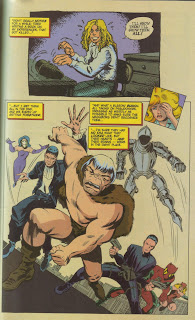

Jenny's story begins in 1930s in America where she is Superman. Literally. Compare this page with the cover of Action Comics 1, Superman's debut, and you'll see how accurately Raney captured the energy and madness of this new art form called the comic book. Jenny "sprang over those imprisoned Depression streets, me and mine, like our lives were being written by teenage kids, and all their guts and lunacy and hope were encoded into every piece of us." This, of course, exactly describes creators like Batman's Bob Kane and Superman's Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster. Plus, check out Jenny's sweet crotchkick!

1930s in America where she is Superman. Literally. Compare this page with the cover of Action Comics 1, Superman's debut, and you'll see how accurately Raney captured the energy and madness of this new art form called the comic book. Jenny "sprang over those imprisoned Depression streets, me and mine, like our lives were being written by teenage kids, and all their guts and lunacy and hope were encoded into every piece of us." This, of course, exactly describes creators like Batman's Bob Kane and Superman's Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster. Plus, check out Jenny's sweet crotchkick!

The 1940s belonged to Will Eisner, who's artwork was so influential that the top industry award bears his name. Jenny is drawn as Eisner's The Spirit, a former detective turned masked vigilante on the streets of New York. Modern audiences might have a problem with reading the original Spirit comics, because The Spirit had a black sidekick named Ebony White who embodied a lot of negative stereotypes about African-Americans. To acknowledge this disparity between Eisner's brilliance and his (admittedly of-the-times) racism, Jenny's 40s adventure brings her up against a plot to gas the inhabitants of the city orphanage because "it's full of black kids." Disgusted, Jenny takes her fight for a finer world back to England, her homeland, because "I don't think American really wanted to be better, back then."

Confession time: I don't know what art style Raney was honoring in his 1950s panels. It looks to me almost like Roy Lichtenstein pop-art, but I know that Lichtenstein himself was influenced by comics of the 1950s and didn't produce his most famous works until the 60s. So if you know what Raney was up to, put it in the comments section. I'm always happy to be schooled in my favorite topics.

Raney was up to, put it in the comments section. I'm always happy to be schooled in my favorite topics.

Jenny's 1950s story is a bitter pill to swallow. When she first returned to England, she got involved with the inhabitants of a more technologically-advanced parallel Earth and dreamed of the better world she could help build with their extra-dimensional science. But that other Earth went to war and shut the doors between our Earth and theirs. "What we lost, that shot at Utopia, that still kills me when I think about it." The 1950s brought the human race forward by leaps and bounds--space launches, vaccines, the Green Revolution--but was also marred by hostility and paranoia, by the Cold War and nuclear terror. There was the promise of Utopia, like Jenny said, but we couldn't overcome the fear and cruelty within ourselves long enough to make it actually happen. A bitter pill, indeed.

And then came the 1960s, comics Silver Age. Raney offers one panel in the style of R. Crumb's underground hippie title, "Head Comix," but the rest of the story is pure Jack Kirby. Kirby co-created Marvel Comics best and most iconic heroes: Captain America, the X-Men, the Fantastic Four, and the Hulk, among others. You can't talk about comic books without talking about Kirby; he's had more influence on the artwork of the genre than anyone else. But like Eisner, he was a man of his times, and Jenny can't help taking the piss out of her Silver Age superhero friends, "dressing as weirdly as possible to make sure the neighbors didn't recognize them... I'm sure they had no idea what they looked like." The 60s was the height of Jenny's superhero career. She operated in public as a champion of the countercultural movement, riding the crest of the wave that was supposed to drown out the old, rotten society she'd left behind in the 40s. This was her second chance at the Utopia she'd lost in the 50s, and now, for the first time, she had a team--she had a culture--whose ideals were in line with her own. The world was ready for her message. It was ready to be changed.

with her own. The world was ready for her message. It was ready to be changed.

And then it all went tits-up. A member of her team overdosed on drugs at a concert and went on a murderous rampage, killing dozens of civilians. Jenny was forced to electrocute him for the sake of the ordinary people caught in his path. The rest of the team couldn't survive grief (or the bad publicity) and had to disband. All of Jenny's 60s idealism crashed down around her, and without their champions, the children of the counterculture disbanded as well.

Jenny goes to bed in the 1970s and wakes up in Alan Moore's and Dave Gibbon's 1980s "Watchmen," itself the quintessential superhero deconstruction that regularly competes with print novels for the most important book of the 20th century. Though almost every comic after "Watchmen" owed something to that dark, bitter morality tale, it's rare to see such a direct homage, partially because Moore has gone batshit insane in his later years and might sacrifice those who displease him to his snake god; and partially because Moore and Gibbons made something so perfect and whole that there wasn't anything any other creators could add to it. And yet somehow, Ellis and Raney find something to add to "Watchmen."

Raney captures Gibbon's style fairly well, but his lines are cleaner, almost more Art Deco, and the coloring is even more lurid and sickly than it is in "Watchmen." But this is a sick, lurid tale of missing children and twisted desires, of want and need. There's no way Ellis can top Moore for crazy, but damnit, he's going to try. In Jenny's 1980s adventure, she's again leading a group of superheroes who are trying to make the world a better place, but these masks had "grown up weird and hungry," lacking the moral compass of her 60s team. Her new friends were selfish, trendy, and spoiled, desiring fame and power but giving little back to the people they've sworn to protect. They're supposed to be investigating a string of murders, single mothers killed in their flats, their babies kidnapped. Jenny discovers that her teammates have been killing the mothers and giving the babies to the hero Firesign, who kills them and sews their parts together to make a "perfect" corpse-baby for his barren wife. Jenny tells Battalion, "All the things we talked about, and it all came down to what they wanted."

So that's what "Watchmen" lacked: Frankenbabies. Thanks, Ellis!

Even for Jenny, who's seen everything, this is too much. She goes to ground again, drinking away the better part of a decade in London's Wolfshead Pub, alone and deeply scarred by a century's worth of friends and lovers who could never measure up to her standards.

It's significant that Jenny was never defeated by in battle or outwitted by supervillains. Super-villains don't even appear in her stories. No, each time she failed to bring about a finer world, her downfall was her fellow heroes: the reporter who gases the city orphanage; the parallel Earth humans who descend into civil war; the macho Silver Age superhero overdosing on drugs; the mad, selfish yuppies killing children in Watchmen London. Jenny believes that the world can and should be saved, but all of the saviors she enlists collapse under the weight of their own human flaws. That is ultimately the reason that comic books still matter to us after all these years, not because they show us mighty superheroes, but because they show us how weak superheroes really are. Done correctly, a superhero comic reminds us just how far we still have to go to produce a finer world. Humans have such power, we've moved mountains and rivers and changed the face of the Earth itself. We are the mightiest species the planet has ever produced, and yet we wander around like we can't tell our collective asses from a hole in the ground, able to master space travel but unable to get clean water to half of our fellow humans. We consistently fall short of our own ideals, not because we lack the power to realize them, but because we are human and therefore flawed.

In some ways, Jenny's story is bleak as hell because it teaches that superheroes--and by extension, everyone else--fail in the end. But maybe that failure isn't as big a tragedy as Jenny thinks. As Battalion reminds her, despite how much and how often she and her friends messed up, "You can still see the stars, Jenny." Life goes on. We can always try again.

Next time, Stormwatch goes to Alabama and battles the Tea Party! Too bad that statement is more accurate than it has any right to be.