Summer doesn't end until the autumn equinox, so technically there's still time to finish my Sandman retrospective.

There's still time!

As always,

SPOILERS abound!

The thing about "The Sandman" is that you start reading it and you

think, "Wow, this is amazing." And then you go on reading it and think,

"No, that wasn't amazing,

this is amazing, I didn't know what

amazing was when I said that first bit was amazing." And then, "What was

I thinking?! I could beat my Past Self with a stout rod, THIS is the

true meaning of amazing."

Then you get to "A Game of You"

and it's like the word "amazing" has crawled off the page, spanked you

in a firm but loving manner, given you head, and made you lasagna and a

martini.

I feel a little bad about grading "The Doll's House" so harshly now. The events in it were clearly important because the series keeps circling back to them, first in "Season of Mists" and now in "A Game of You." It makes me look at "The Doll's House" a little differently, knowing that it was where the series got off the ground in terms of the long narrative. I still think "The Doll's House" is the weakest of the bunch, but I find I don't mind as much that Dream Vortex was so poorly explained, or that the main character was so flat and uninteresting compared to the side characters.

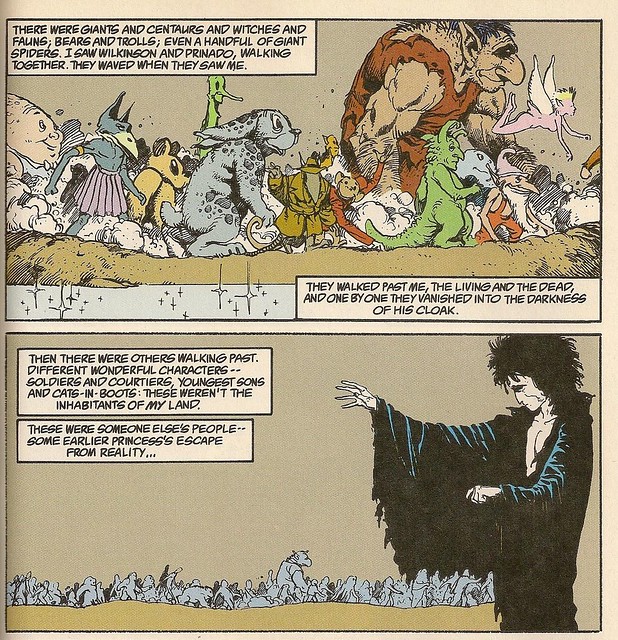

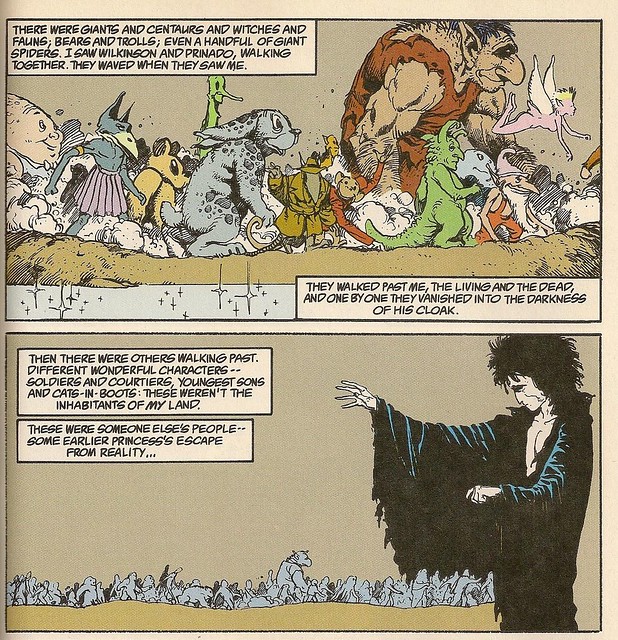

This week's outing, volume 5 of "The Sandman," takes one of those side characters and explores in depth what the Vortex did to her life, both sleeping and waking. In "The Doll's House," Barbie was happily if creepily married to a man named Ken, and in her dreams, she was Princess Barbara, ruler-goddess of a fantasy land under siege by a mysterious evil force known as the Cuckoo. Barbie's encounter with the Vortex leaves her with neither brand-name approved husband nor princess fantasy world. She's divorced, living in a crappy studio apartment in New York, and entirely unable to dream. Her absence has left her fantasy land and its inhabitants without a princess and at the mercy of the Cuckoo.

"A Game of You" opens with some of these inhabitants discussing Princess Barbie's long absence. Her closest companion, a large dog-like creature named Martin Tenbones, decides to go to the real world to find her again. He uses a dream-stone, the Porpentine ( a close relative, as it were, of Dream's ruby dream-stone from "Preludes and Nocturnes) to leave the Dreaming and come to Manhattan, but is quickly cut down by the NYPD. With his dying breath, he passes the Porpentine off to his beloved princess and begs her to save the land from the Cuckoo and destruction.

This is one of the story arcs in which Dream himself doesn't appear much. When Martin Tenbones passes from the Dreaming to the waking world, Dream coldly observes that Barbie's fantasy land, a distant dream-island known as a "skerry," is dying and that he won't do anything about it. That's what skerries do, they live and they die, and this is a story about one's death.

That sounds depressing. And it is. "A Game of You" is the saddest story in the "Sandman" universe. I'd even place it higher in tear-jerk factor than "Brief Lives" and "The Kindly Ones," because at least those stories concern sad events that

matter in grand scheme of the universe. "A Game of You" is

a tragedy that takes place on the margins of the everything, and its characters are rejects from mainstream society whose lives (and deaths) only matter to a very few other insignificant people. Unlike "A Doll's House," in which our main character is very special and immensely powerful, but just doesn't know it yet, "A Game of You" is about people who will never be special and realize over the course of the story just how un-special they really are.

It's dark stuff.

And it is phenomenal.

"A Game of You" is arguably the best "The Sandman" has to offer. It's not my personal favorite, but objectively, this is the best piece of literature in the bunch. It's meticulously plotted and paced, it's characters live and breathe from their very first panels, and it illuminates better than a lot of other storylines what the Dreaming is, who goes there, and why.

The power of the Porpentine enables--or forces--Barbie to return to her dream-land, but Martin Tenbones wasn't the only person who knew how to find her. An agent of the Cuckoo, a man with a chest full of crows named George (the man is named George, not the crows), has been living upstairs from Barbie in New York and monitoring her. When he sees that she has the Porpentine, he cuts open his chest and sends the crows out to menace the neighbors, giving them horrible nightmares in the hopes that they will destroy the Porpentine in order to stop the bad dreams.

I said a couple of review back that "The Sandman" veered away from horror after "Calliope," but I think I spoke too soon. The nightmares the crows give Barbie's neighbors and friends are some of the creepiest images in the series. Barbie's best friend Wanda is kidnapped by comic books characters and threatened with saws and scalpels in a Bizarro-universe hospital; neighbor Foxglove is menaced by her old girlfriend Judy, who we last saw stabbing her own eyes out in the diner slaughter sequence from "Preludes and Nocturnes"; Foxglove's current girlfriend Hazel, who fears she may be pregnant from a drunken one-night stand with a gay man, dreams of a corpse-baby who comes to life to eat her; and neighbor Thessaly--well, she makes her dream-crow burst into flames by looking at it, and then she goes upstairs to murder George with a bread knife.

One of these people is not like the other.

Because I'm a writer and not an artist, I tend not to talk much about the artwork in "The Sandman," but I want to pause here and take a moment to acknowledge the art of "A Game of You." Shawn McManus drew all but one of the issues, and his style is strikingly different from the other "Sandman" artists up to this point. One the one hand, it's a little more cartoony than say, Mike Dringenberg, who did a lot of the early issues and "Season of Mists," but it has this amazing clarity to it that you don't often get even these days in mainstream comics.

You can really see it in the faces of the characters. In superhero comics, often the only way to tell people apart is their hair and costume; the faces and bodies all look the same, especially the female characters, which may as well be traced from a Hustler magazine for all the variety the artists give them. But in "A Game of You," the faces not only look different, they look

distinctive. In the last issue, Barbie meets Wanda's family and you can actually tell that they're all related. This may not seem like that great a feat, but as someone who reads a lot of comic books, I can tell you that it is unusual and rare to see related characters actually look like each other without all looking the same.

As long as I'm talking about art, I have to retract my earlier comment that "The Doll's House" has the worst coloring ever, and shift that comment over to the inking in "Sandman" issue 34, chapter 3 of "A Game of You." Colleen Doran took over for McManus for this issue, and if you look at her original pages, they're great. But George Pratt came along to ink the pages and it came out looking like shit. The artwork was so bad that when DC released the Absolute Sandman editions,

issue 34 was replaced with Doran's original artwork that she re-inked herself.

|

| Good art. |

I don't own that edition, so I'm stuck with the version that both Doran and Gaiman hated.

|

| Shitty art. The more you know. |

There's your comics industry gossip for the day! Back to the story.

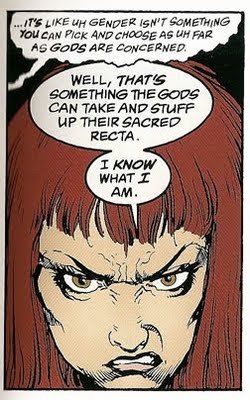

Thessaly is an immortal witch who tears George's face off his dead body, nails it to the wall of his apartment, and makes him reveal all he knows about the Cuckoo. She decides to go into Barbie's dream and kill the Cuckoo, not because Barbie may die if she doesn't, but because you don't get to be an immortal by letting people push you around. To get to the Dreaming, Thessaly pulls the moon down from the sky and forces it to let her, Foxglove and Hazel take the moon's road into Barbie's dream. The three of them get to go because they fulfill the maiden-mother-crone archetype. But Wanda has to stay behind in New York with the comatose Barbie and the face nailed to wall because only women can walk the moon's road and Wanda was born a man.

Imagine, if you will, being a thirteen-year-old girl. (Pick your own, though, don't imagine being me,

I was me, nobody else gets to be.) Imagine being thirteen in a small, fairly religious community with rigid ideas about gender and a streak of anti-intellectualism. In other words, imagine being thirteen in the United States of America. And you're reading a book in which all the main characters are women, two are gay, one is transgendered, one is a witch, and they're all trying to defeat a creature who exploits the angst little girls feel as they mature and become aware of the limitations imposed on them by society simply because they are female.

In feminist circles, this is known as the "click" moment, when sexism ceases to be an abstract concept and is recognized as something that affects you as an individual. The political becomes personal.

I'm not gay, or transgendered, or particularly witch-like, although I did go through a goth phase after reading "The Sandman." It's a bad look for the tropics, Google "sweaty goths" and you'll see what I mean. But this was the first media representation of gay and transgendered people I encountered that treated them as individuals, with lives and stories that were just as important as that of our White Male Protagonist, Dream.

This was also the first time I realized

why it's so important for people to see themselves reflected in the stories they consume, not in an abstract analyze-this-piece-for-symbolism way, but in an explicit this-is-the-point-of-the-story way. All of "The Sandman" is about the importance of stories: the stories we tell others, the stories we tell ourselves, and the stories we live without being aware that we are doing so. "A Game of You" in particular is about the stories that sustain us, sometimes for years, but must nevertheless come to an end. Who are we, both with and without these stories? How do the stories we tell about ourselves create our identities? And how can we learn to move on when we can't move back?

We're still only about half-way through the story. This shit is dense.

Thessaly, Foxglove and Hazel are walking the moon's road; Wanda watches over Barbie's body in New York and chats with George's dead face; and in the dream-land, Barbie has been betrayed by one of her friends and is captured by the Cuckoo. The Cuckoo, as it turns out, takes the form of a ten-year-old Barbie and rules the land from Barbie's childhood home. She takes Barbie on a tour of the house and weaves a spell with her voice, explaining who she is, who Barbie is, and by the way Barbie and the land need to die now if that's all right with her.

The Cuckoo was able to take up residence in Barbie's dreams because of Barbie's deep need for escape from the boredom of her waking life. Her parents wanted her to be a "little lady" and discouraged her from reading superhero comics or playing with boys, so she created a dream based on fantasy books and populated it with living versions of her toys. She became a princess, which is pretty much the only fantasy little girls are allowed to have, and in this fantasy, the Cuckoo was both her mortal enemy but also an integral part of the story. When Barbie lost her dreams due to Rose Walker's Vortexing, the Cuckoo was unable to fly away and go to lay Cuckoo eggs in the minds of other imaginative little girls, and now the only thing that will free her is the destruction of the skerry, which was once her cradle but is now her prison.

So Barbie destroys her dream.

|

| Dream helps. A little. |

The ending of "A Game of You" is a huge bummer, I'm not going to lie. Everyone one of Barbie's beloved dream-toy-friends dies, her fantasy land dies, and the Cuckoo flies away unscathed. The women on the moon's road show up too late to stop any of it, so not only was their journey in vain, but when Thessaly drew down the moon to get them to Barbie, the brief absence of the moon in the sky caused a hurricane in New York City (

which is eerily prescient, I have to say). Dream shows up and offers Barbie a single wish, which she uses to get herself and the other women back home to New York, but when they get there, the hurricane has completely destroyed their building and everything in it.

And Wanda is dead.

The last issue of this story arc is Barbie attending Wanda's funeral in Kansas. She's homeless, broke from spending the last of her cash on a bus ticket to the funeral, and Wanda's family doesn't even want her there. She sits on the edge of Wanda's grave for a while, talking to her about the secret world's that must exist inside of everyone, and as she leaves, she uses a tube of lipstick to write "WANDA" on the headstone over her friend's (male) birth name. The story ends with Barbie at the bus stop after the funeral, remembering a dream she had of Wanda and Death smiling and waving good-bye to her.

I cried the first time I read it. I cried this time. This is a story that makes you have deep, complex feelings, and makes

you think hard about big, scary things. It never stops being incredibly sad and beautiful at the same time, how a person can be irrevocably altered on the inside and yet remain the same on the outside; how people struggle to make their insides match their outsides, so other people will look at a person and see the

true self instead of the self that came with birth and other un-asked-for circumstances; how people leave and die for reasons no one can understand, because the beings in charge of those kinds of things are kind of assholes and don't like to think about the terror and anguish us mere mortals live in because of them. (Seriously, Thessaly, way to be a fucking asshole about the whole thing.)

I think that's why I consider "A Game of You" to be the best of the bunch: because it takes these huge, frightening concepts and arranges them in such a way that not only do you

have to look at them, but you

want to look at them. Most of us don't want to think about how we've changed or how we will change as we get closer to death. Most of us don't like to think about death. But "A Game of You" asks you to look at those things, not because the story wants you to be uncomfortable, but because it wants you to be comfortable. It wants to show you that they aren't such bad things to think about, that this whole being alive thing is not as scary as it seems, though that doesn't mean it doesn't matter. It matters deeply, and that's why you need to look at it.

I don't know, it's a little hard to describe. I'm pretty sure you could read the book yourself in the time it's taken you to read this long-ass review, and I've left out so much! I've left out all the references to "The Wizard of Oz," and what it means for both the kind of story Gaiman is writing AND the significance that story has within the gay community. I didn't touch on the controversy of Wanda's death and how some feel it perpetuates the "Bury the Gays" trope, which I feel is a valid criticism even if I don't necessarily agree with it.

But again, long-ass review. Read it yourself.

Final Grade: A+.