Literally, that is the fear. I'll be somewhere that I want to read something, and I have nothing to read, so I just have to sit there and not read. Shudder.

Obviously, within the comfort of my perfectly Rachel-sized den, where each of my three sit-spots (couch, bed, window where I blog) has a stack of books in grabbing range, this isn't a problem. But as soon as I step out the door, the anxiety begins.

Do I have a book? Does it fit in my purse? Is it too heavy? Will it crush my lunch?

And that's just on a normal work day. If I have to leave for a longer trip, or God forbid get on a plane, watch the fuck out. People who have witnessed me packing--or more embarrassingly, witnessed me unpacking at the other end of my journey--are stunned at the amount of books I choose to haul with me.

But if I don't bring four books on an overnight trip to D.C., what if I finish Book 1 on the train ride down? And then I have to go to Book 2 and I don't like it, so I have to go to Book 3 and I don't like that one either? Then I'd say, "You all laughed at me for bringing Book 4, but lo, Book 4 is needed!"

The point is, my whole right side hurts right now from dragging a suitcase with four books on four separate forms of transportation over the last two days. There's no excuse for this behavior in this day and age. I own a tablet! If I wasn't so cheap, I could just load up my e-reader app with all the books and comics I'd need for a trip to Inner Mongolia and back. But I am cheap, and the free selection on those things is limited to classics. Frankly, I didn't much care for "Jane Eyre" after Lord Rochester was introduced, and I already read "The Hunchback of Notre Dame." Spoiler alert: everybody dies.

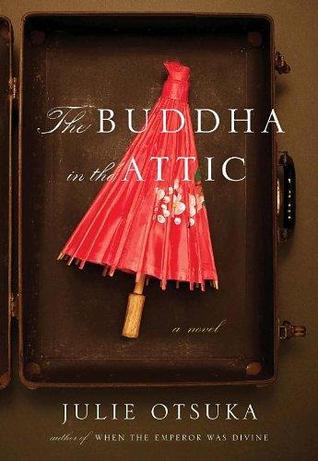

Unfortunately, last weekend when I went to R's parents' house for Passover, my fear manifested itself. I brought Julie Otsuka's "When the Emperor was Divine" and finished it before the train ride was over. I had nothing to read on the way back up. To compensate, this weekend, when the BF and I went to D.C. for his brother's baby's naming ceremony (hi, Big Scientist's Newborn Daughter!), I brought four books. Because Book 1 was Julie Otsuka's "The Buddha in the Attic," and that shit was not happening twice. I finished "Buddha" on the way down to D.C., and Book 2 was sufficient to get me back home to Brooklyn, but if it hadn't been, I had back up.

Unfortunately, last weekend when I went to R's parents' house for Passover, my fear manifested itself. I brought Julie Otsuka's "When the Emperor was Divine" and finished it before the train ride was over. I had nothing to read on the way back up. To compensate, this weekend, when the BF and I went to D.C. for his brother's baby's naming ceremony (hi, Big Scientist's Newborn Daughter!), I brought four books. Because Book 1 was Julie Otsuka's "The Buddha in the Attic," and that shit was not happening twice. I finished "Buddha" on the way down to D.C., and Book 2 was sufficient to get me back home to Brooklyn, but if it hadn't been, I had back up.Both "Emperor" and "Buddha" are very short books, and they deal with kind of the same subject matter, which is why they're getting a joint review. I was in the mood for Asian-themed literature because the BF and I have been watching "Avatar: The Last Airbender" together, and I remembered reading a review of "Buddha" when it was nominated for the National Book Award in 2011, so Otsuka Oeuvre it is!

"Emperor" is about a family of unnamed Japanese-Americans who are forced to leave their home and live in an internment camp in Utah during World War II. The book is told in five parts from five different perspectives: the mother's, the older daughter's, the younger son's, a combination of the daughter's and son's, and finally the father's. The book is more concerned with emotion and tone than plot as it explores the feelings of fear, loneliness and boredom that come with being labeled a traitor and packed off to a camp so the authorities can keep an eye on you.

"Buddha" is also heavily infused with emotion and tone, and the timelines overlap slightly, but it is much more experimental than "Emperor." It's told in from the first-person plural perspective: we, our, us. The "we" are Japanese picture brides coming to America in the 1920s, meeting their husbands, making a life, having children, and eventually being taken away to the internment camps. Although the first-person plural perspective seems like a gimmick at first, it's remarkable how Otsuka manages to keep the whole thing together, conveying a sense of share experience and community while still making every detail unique to a single woman's life experience.

"Buddha" is also heavily infused with emotion and tone, and the timelines overlap slightly, but it is much more experimental than "Emperor." It's told in from the first-person plural perspective: we, our, us. The "we" are Japanese picture brides coming to America in the 1920s, meeting their husbands, making a life, having children, and eventually being taken away to the internment camps. Although the first-person plural perspective seems like a gimmick at first, it's remarkable how Otsuka manages to keep the whole thing together, conveying a sense of share experience and community while still making every detail unique to a single woman's life experience. Both books are, as I said, quite short, but the length works for the type of tight, precise storytelling Otsuka employs. The subject matter is very sad, dealing with a dark chapter in American history that isn't as widely known as it should be. The internment and deportation of Japanese-American citizens during World War II is at odds with the narrative we like to tell of that time, when the country pulled together on the home front to build ships and planes and defeat the evil Axis powers. Images of unwanted citizens assigned a number and packed onto secret trains to undisclosed locations is something the bad guys did, and it's hard to face the fact that the good guys were doing it too.

Final grade for both: A. Recommended for those who like experimental literature, American history, Asian-American history, stories about the immigrant experience, and people who aren't going very far from home and want a really light book that fits in a

purse.

No comments:

Post a Comment